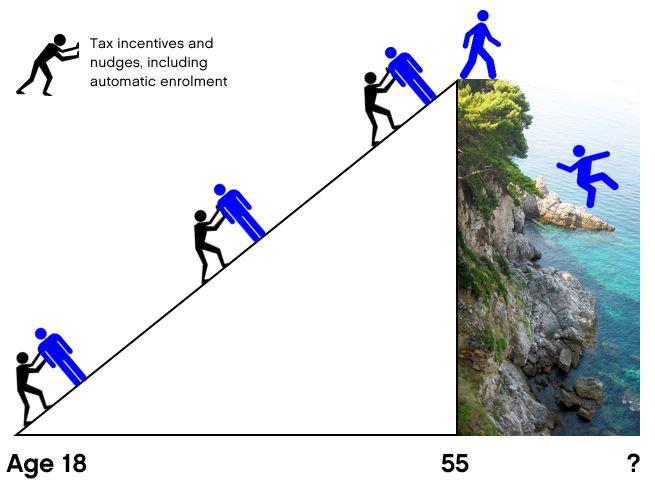

In a new short paper from the Centre for Policy Studies, pensions expert Michael Johnson argues that pension freedoms went too far, ignoring his own policy position (since at least 2010) that freedom is fine as long as it is both supported by market solutions and constrained by limits to choice. In this new contribution to the debate he seeks to balance the paternalistic tradition of UK pensions (now out of favour, he says, with all but the ‘political left’) with the new zeitgeist of freedom and choice. What he proposes is to extend the combination of nudges and opt-outs that characterise the ‘accumulation’ phase, up to the cliff edge of age 55 (at the earliest), into the ‘decumulation’ phase. Better, we say, to support choice than to treat people as beyond either caring or coping – which is what paternalism does. We say market solutions are coming that will engage people and support their choices both before and after retirement.

Michael’s first point is that decumulation, which can start at 55 (but is, he thinks, ‘far too early’), needs default options from providers that deal with both the investment strategy and the appropriate draw (or ‘income’) rate. He calls this ‘auto-drawdown’. This is no different from saying that the industry (whether product providers or advisers) needs to develop an integrated approach to managing the process of living off capital that i) deals with the three risks of capital-market volatility, inflation and longevity and ii) specifies the amount of income that can be safely sustained given how those three sources of uncertainty are being dealt with. When the investment strategy and the draw rate are integrated, risk can be thought of as the chance of sustainability and risk tolerance as the required confidence in sustainability. Risk choices are formed by relating information about possible outcomes, such as forced changes to real spending or how long the capital lasts, to the visualised consequences of those outcomes. Taken together those choices express the utility of the retirement spending plan.

If he is right that it is possible to devise such an integrated sustainable solution for a default fund, we can assume it will also be available more widely. If available more widely, it might also then be more customisable than a default fund can ever be, without necessarily losing economies of scale. For instance, the Fowler Drew drawdown model, which relies entirely on quantitative rules for maximising client utility, uses technology to vary the way standard investment building blocks are applied to different clients with different ages, time preferences for spending, required confidence of sustainability and secondary motives such as bequest. Scaling is at the building-block level rather than the level of each client portfolio and does not require a common draw rate for all clients.

We see the problem as being one of a slow market response to the business opportunities created by the pension freedoms but not an inherent market failure. We could speculate endlessly as to why the response has been slow but we think it has to do with the fact that the kind of stochastic modelling skills required to integrate investment and the draw rate and subject them to quantifiable constraints are located in the insurance industry rather than in retail advice or wealth management. Because it barely exists, it also requires an act of faith that it will be well received by investors and will make a difference to whether they feel supported or exposed. Our experience with over 10 years of drawdown management suggests it is genuinely transformative. If we can do it, it is surely only a matter of time before other solutions appear.

Michael’s second point is that longevity risk needs an insurance solution. But he also rightly sees the two other risks to sustainability, nominal asset return paths and inflation, as much more important than longevity risk until the later stages. His solution is ‘auto-annuitisation’ at 80 as the default, with the right to opt out. Logically, if capital remaining at the late stages is still all assigned to retirement spending rather than to bequest, it will hardly be exposed to much equity-type risk, even if the sustainability requirement is set at a high level of confidence to an age such as 100. In that case, the portfolio should be holding much the same assets as an annuity provider but more of them – because the annuity book may assume an average life expectancy for the pool of say 85 and the uninsured plan has to assume 100. For a given amount of capital left at age 80, an annuity should produce a higher level of spending because it has pooled the longevity risk.

The only problem with this theoretical explanation is that it does not hold in practice because the annuity market is too inefficient. In our experience, an index linked annuity only adds value to a ladder of cash-flow matched index linked gilts if the client lives beyond about 98. Reducing the requirement to annuitise will only make this problem worse. Michael knows this and so his auto-annuitisation suggestion comes with a new collectivist (non-market) structure. He does not say enough about this so-called ‘auction house’ to imply any material advantage over the status quo.

There is in any case no gain in consumer outcomes if the auto-annuitisation ‘pot’ is not itself constrained to a minimum amount by limits on the actual draw during decumulation up to age 80. It will not provide the required protection if the individual chose to opt out and draw more or if the default draw rate proved to be too high to be sustainable (so that the annuity income was also much lower than planned). As soon as you link up the two phases, before and after age 80, you have removed the freedom and choice.

From a financial modelling point of view, the distinction Michael proposes between the phases is inefficient because it makes arbitrary a decision that can benefit from information about market conditions (risk free returns versus risky returns, specific to the time horizon) and also information about the cost of a ‘DIY annuity’ (a horizon-matched risk free portfolio) versus a purchased annuity. It is a continuous decision about the right mix of hedges and bets, based on what maximises spending over the life of the plan. In any solution for drawdown that is driven by the time profile of liabilities, the correct comparison with the insurance market is perhaps that the early years are funded by risk free assets (hedged) and represent a temporary annuity, with the middle and late years funded by risk assets (bets). When the later years eventually become the early years, instead of a temporary annuity (equivalent to leaving the table) they might fund a whole-of-life annuity (equivalent to leaving the casino altogether).

Any preference for paternalism over freedom of choice is also often explained by faith in markets. I’m not sure exactly where Michael sits in this debate but I know I am deeply mistrustful of institutionalised solutions where economies of scale are traded off against creative, heterogeneous market solutions created by competition from multiple sources. The former gave us with-profits funds: the creature of a narrow group of insurance actuaries with common thinking working in regulated firms all having the same economic utility. The market way is different. Solutions will reflect competing ideas about how to apply text-book investment theories, will compete on the use they make of technology and will have many different means of distribution and styles of communication. That heterogeneity is more likely to produce robust solutions that engage and support people through retirement.