Private equity is one of the investment opportunities Fowler Drew clients choose to pass up when they retain us. New research points to why this is sensible.

New research; but not a new idea. The theory that private equity merely exposes investors to systematic risk and return sources that are already latent in public-market returns has been tested in the past. It is tested by seeking to replicate a private equity return time series using public market investment time series. The most common approach is to add leverage to a broad market index like the S&P 500, on the basis that the buy and sell terms are priced off public equities but holdings are much more highly geared. The new research, by Nicolas Rabener (of US quantitative managers FactorResearch) published by the CFA Institute in its blog, Enterprising Investor), seeks to replicate an index of US small-cap stocks, with and without high leverage (within the companies) and with and without a value tilt (a screen to construct and maintain the index). This is not peer-reviewed research and is not detailed so we can’t comment on the indices themselves.

Whilst this is based on US investments opportunities, the nature of the research is such that broad findings ought to be applicable to markets like the UK with well-developed opportunities for investing in smaller companies both listed and private.

What the public-market data has to replicate is a track record for private equity funds. Many fans of private equity investing reject outright the idea that a collection of collectives can possibly accurately reflect investors’ actual experience, on the basis that returns are harder to measure (usually some cash-flow adjusted internal rate of return) and that the spread of actual returns around any average is so wide (wider even than in public markets) as to make the average meaningless. We don’t subscribe to that view. Manager-selection risk is common to any set of active managers. But the logic of choosing an active public equity fund pushes the investor towards managers with more concentrated portfolios (thereby avoiding expensive closet trackers) where the manager-selection risk is likely to be of a broadly similar order. Rabener has used the Cambridge Associates US Private Equity index as a benchmark of actual fund returns. It is compiled from 1,481 US private equity funds’ quarterly returns net of fees and adjusted (supposedly) for survivor bias.

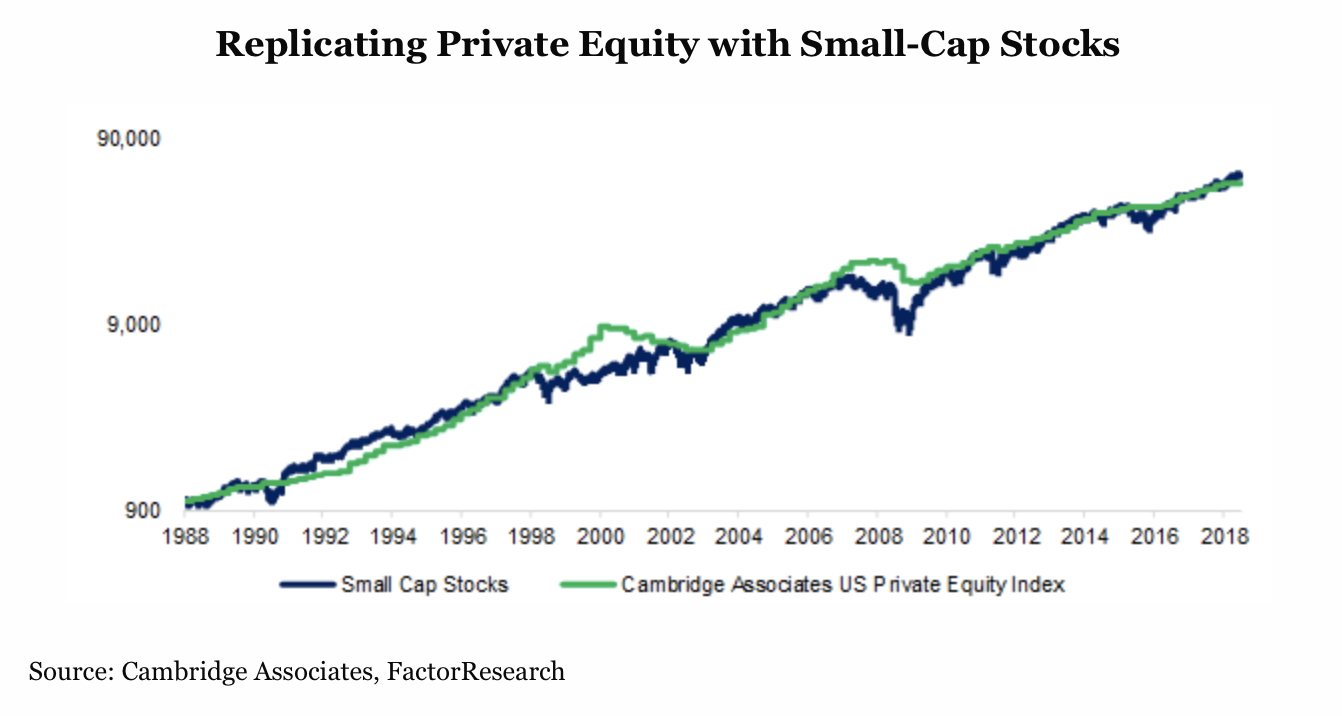

There are few statistics in the article but one graphical output superficially implies that in the US private equity returns can be replicated reasonably well over long periods using small-cap stocks, even without a value or leverage tilt. The ideas that it does not require the selection of small-cap stocks with low valuation of EBITDA earnings and leverage (either in the companies or outside the portfolio) adds to the published research, such as from Harvard Business School (Stafford, 2015), that has previously tested for a segment of the small-cap market rather than the sector as a whole.

This may be not very different from suggesting that the well-documented small-cap premium over the S&P 500 shares some important risk factors with private equity. The author discounts the possibility that the common factor is that the index companies are themselves significantly owned by private equity funds (though only on cursory observation of ownership). Common sense suggests that many of the business-risk drivers of returns are common to all small firms, regardless of how share are held. They are likely to be more vulnerable than larger and more diversified businesses to shocks at many levels: operational, competition, technology, management, financing.

A shared risk relative to large-cap stocks is liquidity, but this is clearly not of the same order between private equity and small-cap stocks, nor of the same type, so comparisons pretty quickly get complicated. One of the reasons we rejected private equity funds and partnerships was that the duration of each ‘vintage’ fund was fairly short. Far from being ‘patient capital’, the lead investors expect to extract most of the value in a window of 5 to 10 years, so there is considerable reinvestment risk (or uncertainty about both the timing and replacement returns). This is a challenge for the end investor and their agent. This form of liquidity has to be considered in addition to the more obvious feature that investments cannot be turned into cash at short notice, which is of course the key difference a listing makes (even if there is a performance cost from forced sales, whether by the fund for investment reasons or by the fund to meet redemptions).

Daily liquidity for listed securities means the most widely-used measures of risk (such as short-term volatility) and risk premiums (such as alpha) are not directly comparable with private equity where valuation frequency is both much less and often relies on estimates. Private equity therefore shares with property the feature of appearing to be less volatile whereas this is an illusion created by the infrequency of changes in the measured net asset value. This is not a mistake Fowler Drew clients are likely to make. They are led to focus more on the uncertainty of outcomes at dates that money is needed or consumed, rather than at shorter intervals where there is no compunction to turn paper losses into realised losses. It is not necessary to conceal short-term price changes or measure them less frequently to avoid emotional responses to market volatility that will tend to reduce outcomes.

The findings in the article are interesting for Fowler Drew clients for two reasons. Firstly, they support our position that private equity is unnecessary because it does not bring a very different set of risk and return exposures from public markets. Secondly, they raise the question whether the risk premium for small stocks is worth trying to capture for individuals, given their alternative of cheaply and efficiently tracking broad market indices. Though we have rejected both, the second is a more open question, forming part of our ongoing monitoring of assets we can, in principle, add to the model. In practice, this is often driven by the reliability of the data, as additions to the modelled opportunity set have two offsetting features: they increase diversification but at the expense of confidence in the outputs of our model. The diversification effect is marginal due to high correlations between market segments within a country. Confidence relates to the data observations (how representative the observed values are of ‘true’ values) but also how they are used in the portfolio structure (given that small-cap stocks are a subset of the country allocation, not a ‘new’ risky asset). For us, the decision is also driven by the availability of low-cost tracking vehicles, which has consistently moved in favour of adding classes.