Bonds, supposedly the risk-reducing asset in conventional portfolio management, have suffered large losses this year. It is clearer than ever that the retail investment industry needs a new approach to managing risk. In this article we explain how Fowler Drew uses risk-free ‘hedges’ instead of bonds to control overall portfolio risk more reliably – and also more intuitively.

Hedging specified cash flows with a ‘matching’ asset is a natural extension of goal-based management, where financial planning identifies and quantifies the cash flows. Goal-focused financial planning has grown in popularity yet investment solutions have not evolved to support it. The planning rightly focuses on outcomes, usually a series of real cash flows to fund spending, over multiple time horizons. But the investment solutions focus on volatility, or the return path at short time intervals.

Dilution versus diversification

Conventional portfolio management aims to manage the volatility of a portfolio by targeting a particular level. Having versions with different target levels allows the industry to gather the maximum amount of client wealth with the minimum amount of customisation. To hit its target it relies on diversification across different risky assets. Hence it is often referred to as ‘Balanced Management’.

A radically different approach, which we adopt, carries the text-book name of Portfolio Separation. It has no equivalent category label in retail investing. It is most widely practiced as part of ‘Asset Liability Modelling’ and ‘Liability Driven Investment’ in institutional investment, particularly for occupational pension funds. Separation theory only needs a narrow range of asset classes because risk is controlled by diluting risky assets with a risk-free asset. The primary form of risk control is dilution, not diversification.

In the textbooks, Portfolio Separation Theorem holds that:

- the most efficient combination of risky assets at any time is common to all investors

- individual investors’ portfolios are differentiated by how much of the risky asset portfolio they hold and how much they hold in risk-free assets

- that mix is a function of their personal risk aversion, itself described by how they choose between a ‘certain’ return (known) and an ‘uncertain’ return (or range of possible estimated returns).

Fowler Drew’s innovation in adopting portfolio separation as the basis of goal-based portfolios was to translate returns into goal-relevant outcomes at the time the money is needed. The risk-free asset can be identified as one, or the only one, that ‘hedges’ a liability, or need, by guaranteeing an outcome that matches the required outcome. There is no uncertainty about its own outcome. That means investors minimise the problem common to diversification: not being sure how different assets will behave in relation to each other. Dilution requires fewer correct assumptions about market behaviour than does diversification.

The risk-free hedge is by definition customised to the nature, time horizon and amount of a known liability. The ‘nature’ of the need is particularly important. Funding future spending needs and wants is a real-terms objective, requiring assurance about future spending power, after inflation. Volatility is a short-term measure of risk and so is necessarily a nominal measure, in money terms. It does not address the fact that the same asset classes may behave quite differently in real terms, over longer periods exposed to the effects of inflation.

Private wealth managers, along with retail investment product manufacturers and distributors, are only now beginning to take on board the inconvenient fact that prioritising volatility leads to the inclusion of instruments that introduce greater exposure to inflation risk: bonds. They were therefore ill-prepared for the likelihood that, after a period of very low inflation and interest rates, the behaviour of bonds relative to equities and other ‘real assets’ would change. Longer-dated bonds over the past year have fallen by around 30%, more than most equities, and for some of the period bond prices have been falling while equity prices were rising. Funds with low volatility targets have lost more money than funds with moderate volatility targets. This is not the behaviour diversification relied on.

Many managers have taken the precaution of shortening the duration or maturity of their bond holdings, so they were less volatile and more cash-like. But the fact that they had to engage in active-management techniques supports the point that the retail investment industry lacks a systematically reliable way to manage risk.

Asset allocation as a dynamic function if time

The distinction between risk as volatility and real-outcome risk points to the natural advantage of private individuals as participants in financial markets: they can hold equities and other volatile real assets to fund longer term needs, while hedging shorter term needs. Portfolio Separation is therefore best applied by time horizon, or the duration of the cash-flow liability.

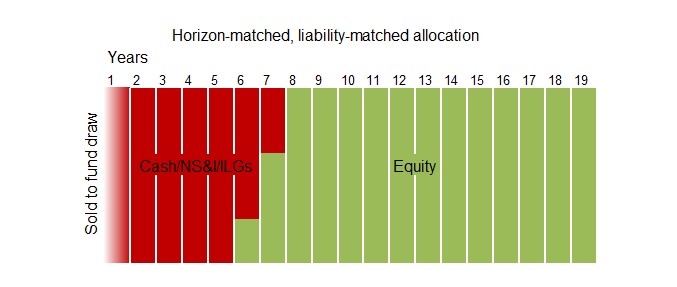

The simplified diagram below shows a portfolio funding a stream of cash payments, such as a retirement drawdown plan, living off a divorce or injury settlement, or a distributing trust. In this vertical organisation of the asset mix, each year of spending, from one year out to 19 (in this case), has its own resources allocation and its own asset allocation (as %) for that resource. Risk-free assets are shown in red and risky assets in green.

The shortest-duration liability, at left, is already 100% in cash, ready to be drawn and spent. Time slices with somewhat longer duration, still 100% risk free, have some exposure to inflation risk and so are held in Index Linked Gilts (ILGs), with durations matching the spending horizon, or index-linked NS&I Savings Certificates. Combinations of cash, NS&I certificates and ILGs can be managed to maximise return for a given overall required duration of the risk free portfolio. The medium-term time slices hold a mix of risky and risk-free assets. Only the long-duration liabilities are matched entirely with equities. The asset allocation is necessarily dynamic because overall duration progressively shortens for any set of cash flows with a finite life. The mix is also specific to risk tolerance. A more risk-averse client would hold more risk free assets spread across more of the time slices.

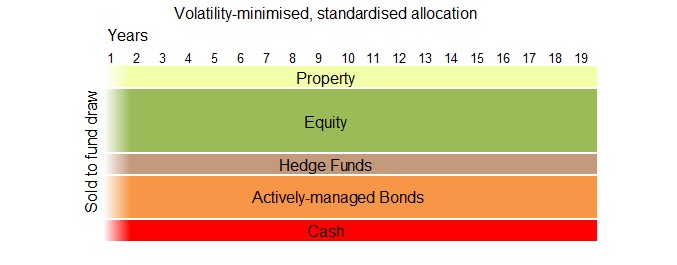

The vertical organisation of the portfolio, by time, contrasts with the horizontal organisation of typical balanced or Multi-asset Portfolio, below, organised by a fixed asset mix chosen to target a particular level of volatility, independent of time. Proportions of the entire portfolio will be sold to fund spending as required. The asset allocation is implicitly stable through time.

Because bonds are the assets in the mix most likely to reduce volatility, it is the proportion in bonds, rather than the mix of other assets, that determines whether the portfolio is categorised as more or less cautious, or more or less return-seeking. The balance here might generally be labelled ‘moderate risk’.

Cost savings

Portfolio separation is much cheaper to deliver than diversification. None of the risk-free holdings are funds (unless a low-cost money-market fund is used for cash) and platform charges may be avoided. Virtually all of the cost is for management of the process.

For portfolios relying on diversification, the holy grail of improving the portfolio expected return for a given level of portfolio volatility can only be met beyond a certain point by adding much more expensive investments than low-cost equity trackers. Since active management tends to be integral to some of these alternatives, a new source of return uncertainty is also introduced. But the entire process for balanced management is usually active because the standardisation it leads to tends to make performance the only differentiator.

Behavioural advantages

When the process is placed in the context of outcomes-driven financial planning, clients see for themselves the advantages in controlling their own behaviour and making better decisions more easily.

- The idea of investment risk being different when associated, say, with distant spending horizons rather than as a basis of meeting near-term spending is entirely intuitive.

- It encourages a form of ‘mental accounting’ that increases composure, because the assets to be consumed during a period of perceived high risk, such as war or recession, are already in risk-free form.

- When equities are doing badly, clients appreciate that they have some time to ‘ride it out’.

- Being able to quantify spending outcomes makes planning more relevant and engaging.

- By treating spending outcomes as outputs of a process, preferably with a quantifiable probability distribution, risk preferences can be revealed directly by clients.

- The collaborative planning process acts as an audit trail of how choices and trade-offs were made, reducing the risk of misunderstandings or dispute.

- Clients choose to take themselves out of the ‘performance race’ that often characterises the choice of adviser and in turn leads to stress and bad decision making.

These advantages are vital if the planning process is to modify people’s attitude to volatility, seeing it as something they may prefer to live with in order to enjoy particular outcomes they want or need. Risk tolerance is then a discovery process assisted by modeling, illustrative iterations and scenarios. It becomes an output of planning rather than just an input. Current practice treats it as an input, independent of the intended relationship with an adviser as navigator. As an input, it often relies on testing of personality traits, as though investor behaviour cannot be modified by information or context. That is a failure of imagination that wastes one of the most important benefits of a relationship with a financial adviser.

You can see for yourself whether information about spending outcomes, coming from interaction with a model, would be likely to modify your own attitudes to how to invest or how much risk to take: test drive our Planner here.

Managing the risk free portfolio

Clients familiar with a liability-driven approach rightly see the management of the high-level mix between risky and risk-free assets as the key decision. The risky portfolio approach becomes much less significant, as long as it is always diversified, both within and across markets. Indeed, the dynamics of derisking, as spending time horizons move closer, could be applied to a range of different approaches to the risky portfolio without losing the risk-management benefits of separation. But that leaves the management of the risk-free portfolio itself as unfamiliar territory for private clients. It is not the same as a low-risk (low-volatility) portfolio, nor as an absolute-return portfolio, as these do not have the feature of hedging quantified cash flows at specific time horizons. How is it managed?

To start with, for it to be risk free it must be largely rule driven, constrained by the discipline of hedging the nature, date and amount of specified cash flows. Our model runs for each client goal give us the bespoke information we need about the individual exposures. But that still leaves us some important areas of judgement. Private clients do not always have access to perfect hedges for their spending so we need to get as close as possible. Factors we take into account are:

- our view of the likely stability of inflation rates over the next 2-3 years

- changing interest rates at the same maturities for different instruments

- the different tax treatment of the instruments.

The instruments private clients can use, organised by ‘duration’ (time to consumption) are:

- Cash held against the very near years of draw. If held by the manager this can actually pay out in line with sustainable draw rates, uplifted by actual inflation. It could be held off platform as individuals can often earn more than deposits in a bank account associated with a platform-based ‘wrapper’. High levels of government guarantees are available only to individual accounts at NS&I, note.

- Money-market funds (open-ended investment vehicles holding say only instruments with under 3 months maturity) are an alternative to bank deposits. They diversify the exposure to individual deposit-takers but introduce management costs that can be prohibitive for small investors.

- Ultra-short gilts are direct alternatives to bank deposits and money-market funds. Tax treatment may make them less efficient, depending on market conditions, unless held in a tax-free wrapper where the different treatment of income and capital is irrelevant.

- Longer years of draw, say 2-7 years out, are exposed to inflation risk and the natural risk-free hedge for these cash flows are maturity-matched Index Linked Gilts (ILG). Note that the inflation uplift will only be treated as tax-free gain if held directly, rather than in a fund. But in any event, it is hard to match liabilities using a fund, which has a different management agenda.

- If individuals were advised to use NS&I inflation-linked savings certificates, issued with 3- and 5-year maturities, these can act as a float, added to (until closed to purchases a few years ago) and rolled over at maturity. In that case the duration of the ILGs held needs to be modified to accommodate the assumed duration, say 4 years, of the NS&I exposure.

As is evident from the above, efficient management of private wealth in risk free instruments is not easily scalable. It tends to require direct holdings (although this can be achieved with a Managed Portfolio Service) and to maximise returns it may require the client to hold assets directly, off platform. Managers are then dependent on collecting holdings data from third parties, not just to report the whole portfolio, risky and risk free, but also to manage the allocations to each. Managers also have to deal with the challenge of earning an appropriate fee on the assets that they ask clients organise, even though they are clearly a critical part of the risk-control process.