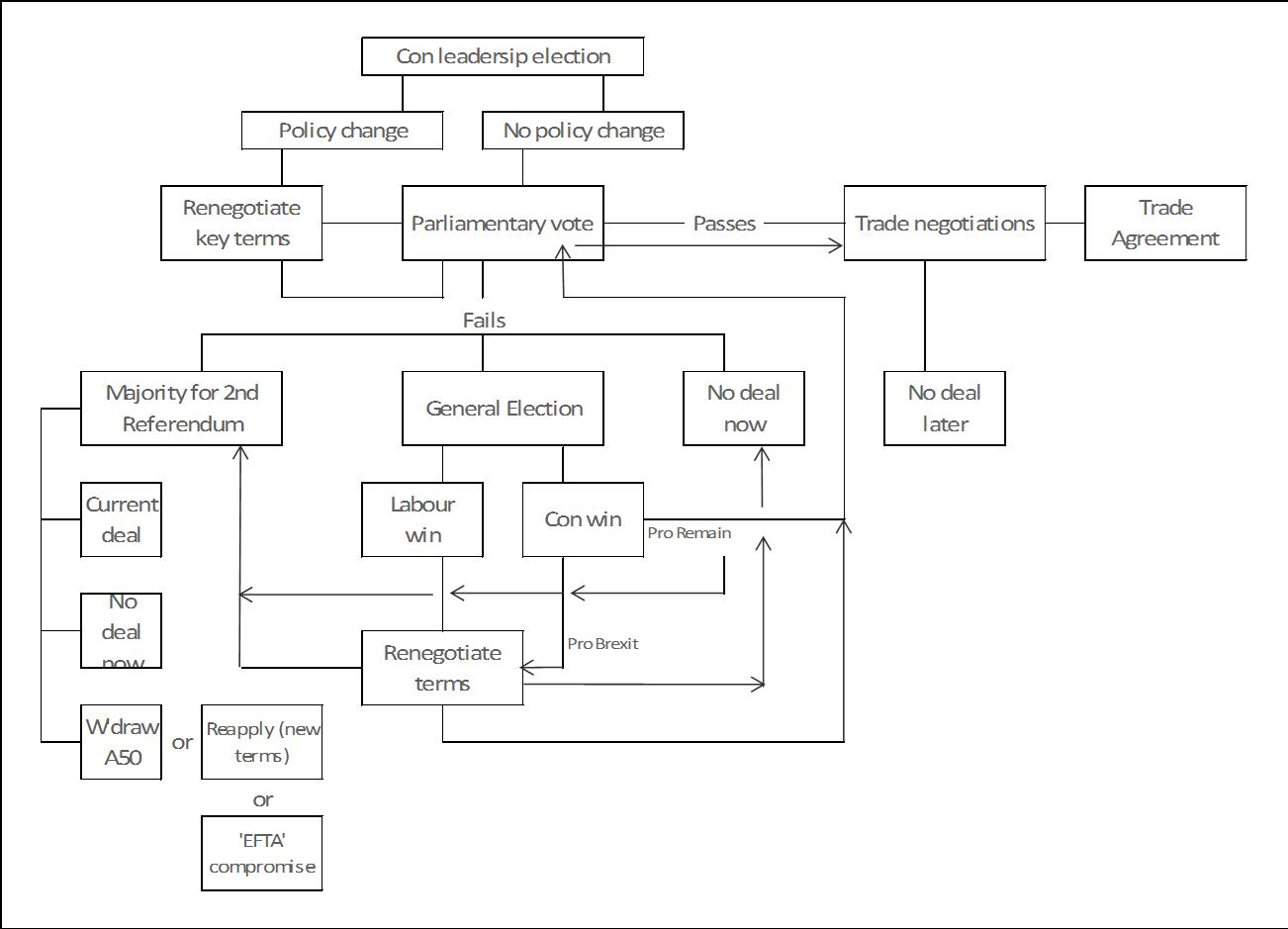

This is my rather crude attempt at a Brexit route map, for the purpose of a bit of game theory. Brexit is no game but to a detached observer it presents a fascinating problem. To anyone with a particular objective, or skin in the game, game theory is an important part of mapping a critical path through the Brexit maze to your preferred outcome. To succeed, you will need to know the rules and constraints; know what the wild cards are; and – like all good game theory – anticipate every reaction to every action. That could get you what you want. But a good war game is also about making sure that what you think you want really is the best outcome for you. Second-order effects may mean that victory in fact undermines the first-order benefits you expected.

Anyone can play but politicians have to. So do business people, who constantly find themselves in conditions of uncertainty (though you will hear them lobbying implausibly for certainty) and always need to plan accordingly. Which is how I came to map out the possible paths. I have no special skills in this area so I’m sure this is not complete. It ignores, for example, random events that war games ought to try to anticipate. The logic applied to the different paths is, as best as I can make it, objective. My preferred outcome, or that of the firm if it had one, could be any one of those set out.

The paths have been mapped to be consistent with the rules of the game, as now defined. The rules are not the same, note, as when the negotiations started.

The first rule is that the exit treaty and the future trading relationship are now discrete events. ‘Sequencing’ was the battle the EU won in the earlier negotiations. We mustn’t mistake the stage we’re at now as a Brexit deal. It’s only half a Brexit: the divorce, not the future relationship. How the EU managed to win this strategic advantage is a matter of debate and poor statecraft may or may not be to blame. It became an inevitability, though, when the UK team conceded that a transition period was necessary. From that point it could no longer be a case of ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’.

The second rule that was also not known about when the Brexit negotiations began is that Parliament gets a meaningful vote, thanks to the Supreme Court. That also constrains the possible paths for all players.

The wild cards are held by the EU. Any one nation and also the European Parliament can veto any deal, and that applies to both the divorce terms and the future relationship.

The possible outcomes can be identified, as follows:

– no deal now

– divorce followed by a successful trade agreement

– divorce followed by failed trade talks – or no deal later

– withdrawal of Article 50 on unchanged terms (like Bobby Ewing’s dream, it never happened)

– remain in the EU but on revised and more onerous terms.

The possible steps (in no particular order) that may or may not be needed are:

– one or more Parliamentary votes

– a second referendum

– a change of leader without a change of government

– a general election leading to a change of government.

Hint: the game is not won by being right about the eventual economic impacts of one or other outcome, even though that may colour your own preference. All that counts is other people’s opinions about the likely impacts. These are of course subject to influence during the game, so possible changes in pubic assessment are a reaction that need to be anticipated. Like a beauty contest, the winner is the one most judges think is most beautiful so correctly guessing the outcome is about guessing what the judges think.

Because game theory applies, we have to imagine how to play everyone’s hand, not just our own.

Let’s start at the top. The ball is in the Conservatives’ court. But before the Government tables a vote on the draft divorce agreement, as required by the Supreme Court, there is a possibility of a leadership challenge. For the challengers, the dilemma is not just whether they can successfully force a leadership election (a numbers game for both calling and winning it) but whether they really want to. They only get one crack at this in any 12-month period. They may do better to bide their time until after the Parliamentary vote.

They may not be able to muster the numbers (48) to call a leadership election because some Brexit-leaning MPs may prefer the soft option of a transition period. This (not an ideal analogy) is the ‘Munich option’: you pay the price of the transition period to buy time to prepare, if necessary, for no deal later, in much the same way that history has come to judge appeasement at Munich as essential to buying vital time to rearm.

Even if they are able to change their leader, they are still the same MPs faced with the same requirement to vote on the existing terms. As long as Parliament has the say, and unless the change was one that altered the intentions of the other parties (unlikely in this case), the change of power within the Government does nothing to make no deal more likely, were that in fact their real intention. But they would have the opportunity to use the change in power within the Government to exert pressure on the EU to make revisions to its terms, even if they were the same revisions the May team might have already sought.

In summary, the opportunities for MPs preferring ‘no deal’ to this ‘bad deal’ are heavily circumscribed. Which is why it may not happen, or not at this stage.

For Conservative remainers, the appropriate tactics (beyond fighting off any leadership challenge should it arise) depend on whether their objective is approval of the current deal or its defeat, on the basis that defeat will pave the way for a majority in the Commons for a new referendum.

Though a new referendum could prevent Brexit happening at all, which might well be the ultimate objective for some, the risks with a referendum are considerable. Not only might it not confirm their hope that the public have turned their back on Brexit, but it may require multiple questions and either two voting rounds or transferable votes that make the outcome much more random.

The tactical advantage of a referendum probably depends critically on whether the EU is prepared or even able to offer the status quo, Article 50 withdrawal, as an option – something that the ECJ might have to determine. Returning to the EU without the benefit of our rebate or other opt-outs is a very different option. It is also one that puts the EU itself in a very different light, itself affecting the outcome. Faced with the two extremes of no deal and unaltered EU membership, the third option of the transition to trade talks is not obviously transferable to one, rather than the other, extreme. Though I’ve included an EFTA-type option in my route map, I’m not sure that is really different from the divorce deal.

This logic treats all options as being unaffected by the referendum itself. But the very act of calling a referendum affects the transition arrangements. It eats up time that might otherwise have been spent on different preparation for the future relationship. It reopens public debate about the economic impacts of no deal – which has been the single most important difference in attitude to Brexit. If Lord Ashcroft Polls’ post-vote sample of 12,000 is representative, 77% of remain voters thought the economic impact of Brexit would be ‘disastrous’ whereas 69% of leave voters thought it ‘didn’t matter much either way’. They can’t both be right. Subsequent debate has generated more heat than light but financial markets are a more objective gauge of probabilities and they have been remarkably sanguine.

The fact of a second referendum also affects the likely impacts because the clear message to business of our inability to move forward decisively to a transition period is to assume the worst and prepare for no deal. There is less to prevent, even if no less to fear, if the impacts have already occurred and may never be fully reversed. It is likely that this is already happening (there is evidence of it in many industries) but that does not yet mean the effects are actually less than feared. But with more time it becomes harder to discount the way firms’ adjustments are apparently not affecting output or jobs as much as feared.

Back to the Conservatives and the vote on the divorce. There is probably one missing piece of information that needs to emerge and probably will: the extent to which we are legally bound to cede actual or effective authority over the relationship after the transition period to EU bodies, assuming the trade agreement talks have failed. The is the potential significance of the so-called backstop.

Notwithstanding legal opinion, which may not be trusted sufficiently, this is the main issue that could require the UK to force the EU back to the negotiating table. The alternatives would otherwise be no deal or a referendum. But if the reason for the referendum is the fact that the divorce deal cannot pass because of the backstop, the existing divorce deal cannot then be an option in a referendum. This leaves only no deal and EU membership as alternatives. As noted, a binary vote is simpler and is more likely to produce the outcome remainers want. Therefore the best way for the remainers to achieve their end is to try, and fail, to persuade the EU to give up their effective veto on our eventual exit and thereby make a referendum the only way out.

What about Labour? We know they don’t want to be drawn into a debate that advertises the split in their own ranks over Europe, but what do they want as an outcome? Is there even such a thing, or will MPs themselves be split idiosyncratically (not even by factional loyalties) over the best outcome? Are individual MPs more interested in what their constituents think than what the party thinks about Brexit? Labour supporters in the country are split over a number of attributes of the EU, particularly immigration, but probably the least important in the country is the one that looms large as an issue for the party itself. Labour wants to have another push for broad public approval for a socialist agenda. But it is this that the EU most threatens, because a level playing field for competition prevents state subsidies.

There may be no good outcome for Labour on Brexit but Brexit might be able to deliver what they do want: a chance to win power. Labour sees Brexit as potentially offering a means of doing so quicker than fixed-term elections allow. So this may dictate how they choose to navigate the Brexit paths.

The opportunity to force an election relies on first voting against the current terms. Since Parliament might also reject any solution that leads to no deal now, it leaves just the alternatives of a referendum or a general election. Labour is opposed to a referendum. It should be, if by ruling it out it can close off the only competition to an election.

This brings a different dilemma. Exploiting this situation, both when it comes to the Parliamentary vote and the alternative of a referendum, makes it look like it is willing to sacrifice the national interest for party interest: a power grab that might backfire when it comes to those elections.

This dilemma is crystallised as soon as Parliament has to vote on the divorce terms, even without the parallel rejection of a referendum. After all, the public do not necessarily see the Labour Party’s stated policy for Brexit as being fundamentally different from the divorce terms on the table now. Nor is it obvious outside the party why Labour might be able to negotiate a significantly different set of terms, as supposedly being a more trusted negotiator. The EU presumably has no illusions about the split in the Labour party on Brexit and is aware of the possible conflicts to come with a socialist government in the UK, or the awkwardness of the UK doing all the things fiscally ‘irresponsible’ things the EU tells Eurozone members they cannot be allowed to do.

The alternative Labour tactic is to vote the present deal through, which it probably can do. This would presumably be a case of enlightened self-interest, relying on the country to remember and reward its sacrifice of immediate electoral advantage.

What about the other parties at Westminster? I have attempted to follow the same logic but I may well have missed some subtleties in their objectives.

The DUP’s objectives appear most difficult to achieve, as they require every one else to fail. The backstop is there because of both the Republic of Ireland, holding the joker, and Northern Ireland. Each focuses on minimising friction at their common border. We do not really know how strong this common objective is. Economically, the border that most concerns the Republic is the sea crossing to the UK, not just because of trade with the UK but because the UK is the Republic’s land bridge for 80% of its trade with the EU. Recognising this, the EU has promised funding for new sea routes to EU ports but at twice the time and much greater cost. The common border is of political significance, more than economic. Game theory requires assessment by all the other parties of the extent to which the political significance of any friction to trade across the border can be managed down. This is a process that involves the DUP but is not within their control, as it occurs outside Westminster where their leverage resides.

The spoiling tactics the DUP can use in Westminster are to force either a referendum or an election. Only the first directly serves their objective of minimising any change to the status quo, but with the same caveats as we have noted about the unpredictability of this path. The SNP’s objective is also the status quo and so its path also leads via a referendum.

I have not allowed in the possible paths for any intervention by the House of Lords that would alter these paths, rather than simply direct the actual path in terms of an alternative already mapped. This gap might be significant, I feel.

War games require assessment of how the EU will now play its hand. In terms of first-order effects, the EU has played a good game. But it faces a dilemma similar to Labour’s. It is playing a good game if what it thinks it wants is to punish the UK ‘pour encourager les autres’. Or to be more precise to discourage anyone else from leaving. As Boris Johnson rather crudely pointed out, success is in fact failure if the effect is to make other EU members even more reluctant to trust the Commission and if it encourages less federalism or more reform. Ironically, failure for the Commission would then look quite like the success that eluded David Cameron, and in doing so triggered the UK Referendum. Would you therefore bet on more enlightened self-interest from the EU? That may be affected by the presence of the wild card. Might the EU be indifferent to uniting states in fear of where they too may tread, as long as the course it plots has to survive a veto by any one. Blame the joker, in that case.

The dilemma that victory may spell defeat is perhaps even more relevant when it comes to reacting to no deal. That is when the choice is starkest between reasonable cooperation to minimise damage to both sides and allowing, or even encouraging, hostilities just to make a point. However, the attitude of the Commission may prove less relevant than the attitude of individual governments, the French being most exposed to the cost and benefits of chaos in the channel ports that it can itself control.

The EU’s approach to statecraft is not only being watched by the 27: the UK public, who may yet be consulted again in two of the possible paths, may be less willing to trust the EU as a partner, in trade talks let alone in returning to full membership, if it appears to be too hostile. That may apply whether the ‘bad partner’ is seen as being a single nation or the Commission itself.

There is one external player influencing the game: the WTO. If the outcome of no deal now is to emerge as a matter of choice, rather than by default, the attitude of the WTO to fast-tracking the UK as a member in its own right and the basis for appointing EU quotas are variables that could affect what the no deal now option looks like.

In thinking about the challenges, I was reminded of my favourite board game, Diplomacy. Set in Europe in 1914 before hostilities began, its success as a game depends on the balance between the rival European imperial powers and by the carefully crafted constraints. Not having studied history, geography or politics, it may be the principle means by which I learned what little I know about statecraft. Forgive me if those limitations show.